600 years.

By the Lord Harry, not many of us 'Band of Brothers' left.

The English are so very like the French. I know, I know, that is almsot a heretical thing to say, but two nations that have always coveted one another's lands have to have more in common than differences.

The Battle was a reknowned event for both countries, and much remarked upon in the past 600 years. I am grateful to not have to retell it as Gildas the Monk dropped by for a swift half after addressing the crowd in Anna's pub down the road.

They Say Azincourt;

We Say AgincourtAgincourt, with the assistance of Shakespeare, has become renowned as one of the greatest English (and Welsh) victories in battle. I have a passing interest in that it is just possible, though not at all certain, that I had a relative in the English ranks. Henry V, King of England, was young, tough (he had taken an arrow in the face in a battle at Shrewsbury and had it pulled or cut out, but lived to tell the tale), smart, energetic and had a gift for man management. He was also fanatically pious by our perspectives, and had, I think, the total belief that if his cause was just, he would have God fighting on his side then he would prevail.

And he had, I think, a fanatical belief that he was indeed entitled to the French throne and his cause was just.

In the summer of 1415 Henry had landed near and with the intent of taking the walled city of Harfleur, and thus using it as a base from which to pursue his further campaign. He landed in a France which was split by civil war between the Armagnac and Burgundian factions, into which the English has actually been sticking their noses, just to keep the pot boiling, largely on the Burgundian side, I believe.

France was thus dangerously divided. The French King, Charles VI, was mad as a hat stand, and his heir, “the Dauphin”, was just 18 and considered not up to command of a united French army.By October Harfleur had finally fallen but the campaigning season was drawing to a close. Henry could have left for England from Harfleur, but that might have looked suspiciously like a failed campaign, and determined to march his men to the then British held Calais. The English army trudged along and started to run out of food. By the evening of 24th October it was clear that a huge French army blocked his passage to Calais,...

and there was no option but to fight.

Significantly, it was raining heavily. The English army was about 6,000 – 6,500 strong. Much greater controversy surrounds the French number and disposition of the French, but the best guess is somewhere around thirty to forty thousand, around six to one. One contemporary has the figure at 50,000 but even if that is true it is unlikely all these troops were on the battle field.

On the evening of 24th October the two armies faced each other in a standoff. The fields across which they looked were newly ploughed sowed, and the soil was the thick clay of the Somme.

Before dawn, the pious Henry celebrated his customary three masses, and at first light the two armies resumed their battle formations. After weeks of campaign and then forced march the army would have been bedraggled to say the least, the armour of the men at arms and knights dull and suffering from rust and clothes filthy. Not so king Henry, who appeared amongst his men in the clever mix of royalty and the common touch.

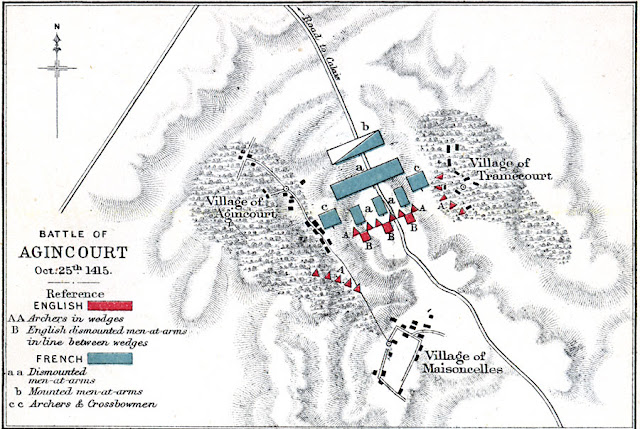

Henry made what is recorded as a superb speech, rallying and inspiring his troops with a common touch and shrewd psychology. It is recorded that it was Henry who told them that the French intended to cut the two forefingers off any captured archer, but it seems this was probably clever propaganda, because it is more likely the French would have simply killed the archers, who were both feared and hated because of their effectiveness, their low birth and their lack of chivalry.The English formation provokes great debate but I think the probable one is the generally accepted one. The main force of some 1,000 – 1,500 heavily armoured men at arms stretched along three or four deep with the archers on the wings. One of the issues about the French order of battle is: where was the cavalry? I think it is likely that the main French cavalry force was at the rear.

For some hours the two armies stood still. The French had no particular reason to attack. All they had to do was block the way to Calais. Fear and hunger would do the rest.

Perhaps around 11 am, Henry made a move to break the deadlock. According to some chroniclers he made a fine speech full of rhetoric as he ordered his army forward. The French force was so overwhelming in number that the question can rightly be posed ........

not “how did the English win?” but “how did the French manage to lose?”

There are a number of reasons…One was the battlefield was too small to accommodate all these men on foot, so other compromises had to be made. It seems that the French had about 4,000 of their own archers and cross-bow men. In the initial battle plan they were supposed to give covering fire and harass and suppress the English archers.

But with so many important noble men on the field all vying to be at the front there was no room for them (the archers) at the front of the army.

Next, the size of the force and the lack of overall command also must have slowed decisive acts and communication.

There was also Armagnac versus Burgundian rivalries and splits within the main French cavalry force, and personal rivalries too.

And it seems that when the English attack was launched, only part of the cavalry responded, less than 500 men. And they were to ride straight into the face of the English.

And thus the great tragedy of Agincourt began.What the plate armour could not protect was the horses of the knights in the charge, and it upsets me terribly to consider the damage the hail of arrows must have done. I will not dwell on that save to say that the charge was a disaster and must have served only to churn up the already muddy field. Those very few brave French knights who actually made it to the English archers were dragged down amongst the wooden stakes and finished off in short order.

As many before me have observed, the English archers had no counterpart to a chivalric code; and they knew that if they lost they would be worthless and not ransomed, but simply killed. Still they struggled on through the sucking mud. Behind them, the second huge battalion of French men at arms began the long trudge too, the sodden field ever more churned up.Worse, the mud was a killer. A knight in plate armour who fell in the glutinous mud would have been stuck, sucked down as if by magnets because of the suction on his armour. If he couldn’t get his helmet off he would have drowned or suffocated.

Men at arms must have been slipping and falling all over the field. I think there was a collapse, and a wall of stranded French men at arms, and as the thousands behind pressed on the tragic barrier grew. All across the line piles of dead and dying start to build up in the press, with men being crushed and asphyxiated in the chaos –

less a battle than colossal crowd disaster

- as the men in the vanguard slipped and fell and tripped over, and the endless press of men kept coming from behind. Men fell and were crushed by the relentless press and great heaps of men built up.It was a battle for survival, kill or be killed. The English finished off the stricken and helpless French with daggers, war hammers and the lead hammers they had used to hammer in their staves. Without saying too much about the brutality with which they did this, this partly explains why it proved so difficult to identify many of the dead knights once they had been stripped of their chivalric emblems. Their faces were smashed.

There is also the matter of the fact that towards the end of the battle the Henry gave the order to massacre all but there must important prisoners there was the rumour of a possible second wave of attack from the French. This the English archers did with alacrity. Some suggest 2000 men met their fate in this way.

Agincourt, then, is not simply of a battle, but in a way of a catastrophic accident. For Henry it was proof he had the righteous cause and God’s support.The cost? It is as ever difficult because the sources differ.

The English probably lost no more than 400 men.

As for the French, it is difficult to know. Author Bernard Cornwell suggests 5,000 but my sense of the catastrophe is greater. It cut a swathe of death through the nobility of northern France, and wiped out very many of the Armagnac leaders. Hardly a family was untouched and some lost fathers sons and cousins. Many wives and mothers waited for months without news of the fate of their loved ones, before reluctantly concluding that they had been slain in the battle.The English can indeed celebrate Agincourt as an extraordinary victory against all odds.

And yet I am bound to say I look on it with a touch of sadness rather than triumph.

Unlike a battle like Trafalgar where I can see the point, I can’t really see that it achieved much at all, and the terrible death toll of man and beast seems to my now middle-aged perspective a tragedy as much as a triumph.

I would rather advance on my French counterpart armed with a glass of vin de pays and some fine cheese than a war hammer.

I have to agree.

Such is the perspective of the older.

Let us raise a Tankard to the French foe.

Pax.

Interesting to read about it again - well put.

ReplyDeleteFew bother to recall, but 'tis worth the effort.

Delete